Drawing machine: Descent Into Madness

This project started as a simple question: what if a plotter didn’t draw on paper—what if it drew on an iPad, with an Apple Pencil, and we could “close the loop” digitally?

Instead of filming the drawing with a camera and doing computer vision, we capture the stroke geometry directly from a web canvas, stream it to an ESP32 over WebSockets, and have the machine redraw it. Once you have that pipeline, you can replay drawings, transform them, and do something I couldn’t stop thinking about:

The game of telephone, but with drawings. Let the machine reinterpret the input each round until it drifts into something else.

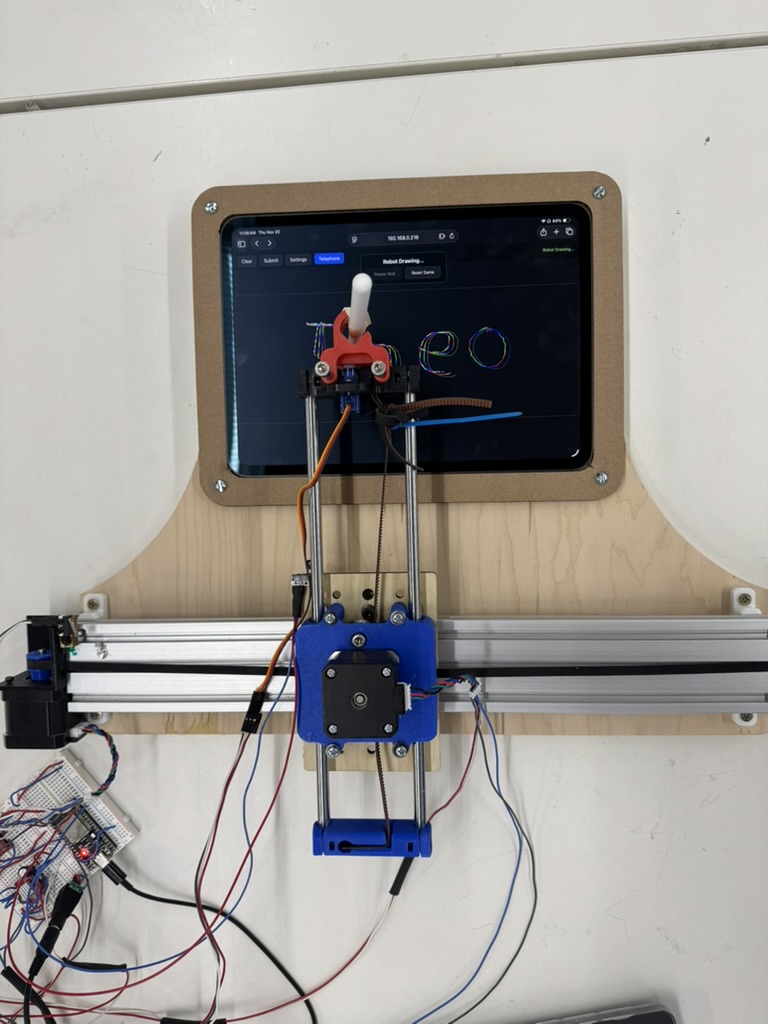

The plotter drawing directly on an iPad. The UI is served from the ESP32 and streams points over WebSocket.

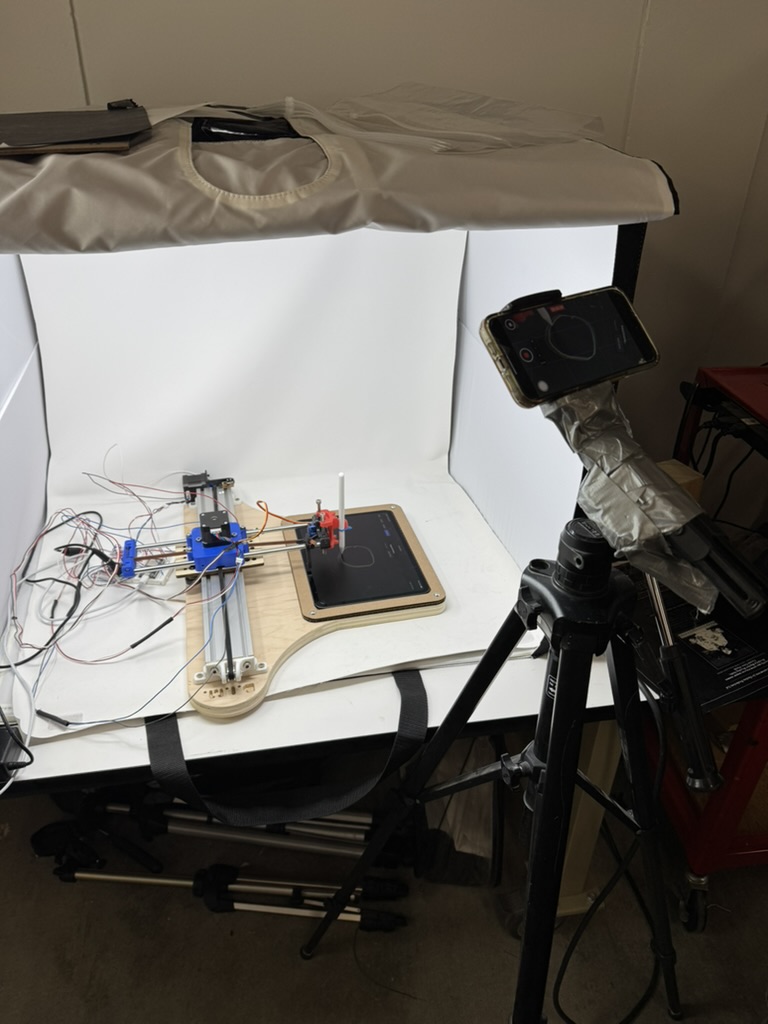

Test setup: plotter + iPad in a lightbox, with a camera rigged for documentation (and debugging).

Front view: X gantry, Y carriage, iPad mount, and the Apple Pencil end effector.

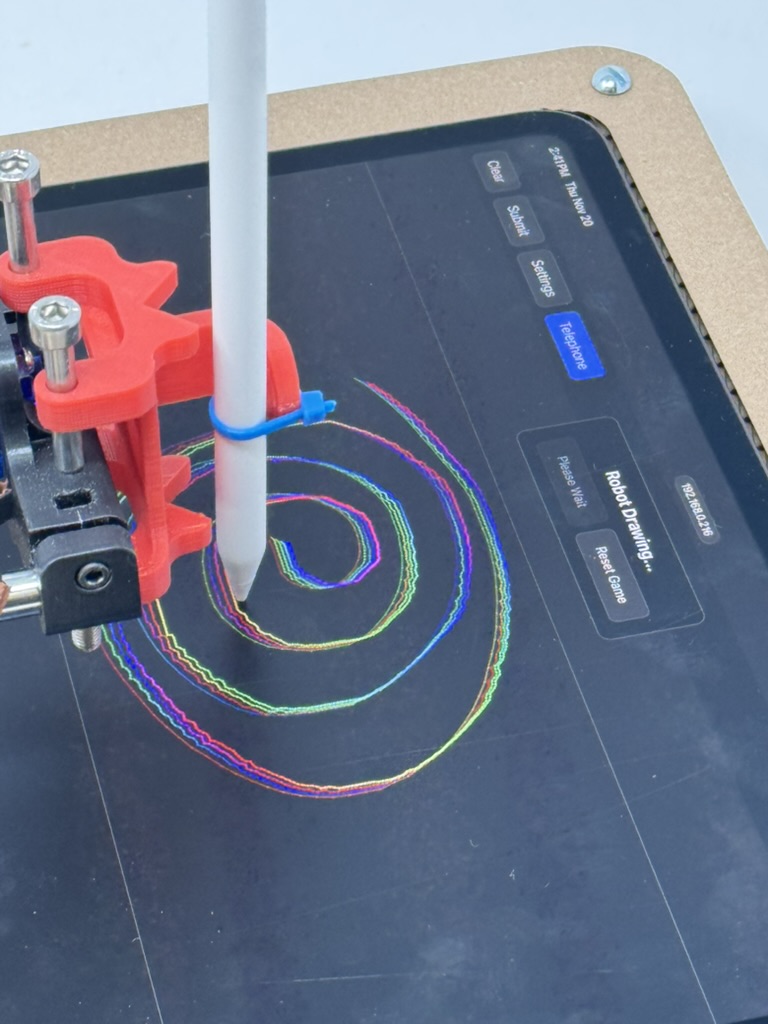

Close-up: the Apple Pencil mount drawing a spiral. The multicolor lines are from replay/iteration mode.

The core idea: a tight digital ↔ physical loop

At a high level, the system is:

Browser canvas (strokes) → WebSocket → ESP32 queue → stepper motion + servo → iPad drawingThe “telephone” part is what happens after a round completes: you take the stroke list, optionally transform it, and feed it back as the next round’s input. Do it enough times and you start to see drift, artifacts, and reinterpretation.

Hardware (what the machine physically is)

This is a pretty classic plotter architecture, with one twist: the “paper” is an iPad.

- X/Y motion: a rail-based XY stage driven by two steppers (one per axis).

- End effector: a servo-controlled Apple Pencil mount (pen-up / pen-down, plus a tunable down angle).

- Repeatable origin: one limit switch per axis to establish a consistent home position.

- Microstepping: the firmware is configured around 16× microstepping for smoother motion and less visible “stair-stepping.”

The iPad mount matters more than you’d expect. Pencil angle, pressure, and height all change whether a stroke actually registers. Once the mount is rigid, you can treat the iPad like a normal drawing surface.

Firmware + UI (the ESP32 is the whole stack)

The firmware is a single Arduino sketch (plotter.ino) that does four jobs:

- Joins Wi‑Fi.

- Serves a full-screen canvas UI over HTTP.

- Accepts drawing + control messages over a WebSocket endpoint (

/ws). - Drives the steppers + servo to execute the queued motion.

Repo: https://github.com/theotarr/plotter

The WebSocket protocol: tiny, boring, reliable

On the wire, a drawing point is a single line of text:

<xSteps>&<ySteps>-<pen>xSteps,yStepsare integer step coordinates (microsteps).penis1for down and0for up.

This intentionally avoids JSON: it keeps parsing simple and fast on-device.

The ESP32 keeps a ring buffer of commands and replies with ACK/FULL so the browser can do backpressure:

// (excerpt) queue + ACK/FULL flow control

constexpr size_t QUEUE_CAPACITY = 4000;

bool queueTargetSteps(int32_t xSteps, int32_t ySteps, bool penDown) { /* ... */ }

int processTextPayload(const char *payload) {

// cmd:* handling omitted...

// Parse drawing coordinates (format: "x&y-pen")

int32_t xSteps = atoi(payload);

int32_t ySteps = atoi(amp + 1);

bool penDown = atoi(dash + 1) > 0;

if (queueTargetSteps(xSteps, ySteps, penDown)) return 1; // ACK

return 2; // FULL

}On the browser side, each point send waits for ACK, retries on FULL, and has a timeout to recover from dropped messages:

// (excerpt) reliable point send

websocket.send(payload)

const result = await new Promise((resolve) => {

ackResolver = resolve

setTimeout(() => resolve('TIMEOUT'), 2000)

})

if (result === 'FULL') await new Promise((r) => setTimeout(r, 100))Calibration: turn a canvas into a physical coordinate system

The machine is only useful if the same screen coordinate hits the same physical spot each time.

The UI includes a calibration workflow:

- Jog the head to the top-left of the drawable area and save it as TL.

- Jog to the bottom-right and save it as BR.

- Persist those bounds to

localStorage.

Then every stroke point is mapped through that rectangle:

// (excerpt) map canvas pixels → step-space via saved bounds

const w = canvas.width / currentDpr

const h = canvas.height / currentDpr

const rangeX = calMaxX - calMinX

const rangeY = calMaxY - calMinY

const normX = pt.x / w

const normY = pt.y / h

const targetX = Math.round(calMinX + normX * rangeX)

const targetY = Math.round(calMinY + normY * rangeY)One subtlety: browser canvases are “Y increases downward,” but the plotter is “Y increases upward.” The UI compensates so “up on screen” is “up on the machine.”

Homing: finding zero you can trust

Each axis homes by running toward the switch until it triggers, then backing off a small buffer so it isn’t held against the switch:

// (excerpt) homing routine

void homeAxis(AccelStepper &stepper, ezButton &limitSwitch, int direction) {

stepper.setMaxSpeed(250.0 * MICROSTEP_MULTIPLIER);

stepper.moveTo(direction * 100000 * MICROSTEP_MULTIPLIER);

while (true) {

limitSwitch.loop();

if (limitSwitch.getState() == LOW) { stepper.stop(); break; }

stepper.run();

}

stepper.setCurrentPosition(0);

stepper.move(-direction * LIMIT_SWITCH_BUFFER_STEPS);

while (stepper.distanceToGo() != 0) stepper.run();

stepper.setCurrentPosition(0);

}Once homed, everything is expressed in that fixed coordinate system, which is what makes calibration meaningful across sessions.

“Telephone” mode (iteration as a feature)

The UI has an experimental game mode called Telephone:

- You draw a round.

- The robot replays it (often with a slight aesthetic shift).

- While it’s replaying, you can keep drawing—those strokes become the next round’s input.

- Repeat, and watch the drawing drift.

Two pragmatic tricks made this feel good:

- Point thinning: ignore tiny movements so the robot doesn’t attempt thousands of micro-segments.

- Idle detection: the ESP32 sends

status:idlewhen the steppers and the command queue are empty, so the UI can transition rounds cleanly.

The problems we actually had to solve (a short postmortem)

- Smooth motion beats fast motion: microstepping and acceleration tuning mattered more than raw speed.

- Mount rigidity is everything: the iPad mount and Pencil alignment determine whether strokes “take.”

- Limit switches need love: debounce, wiring, and mechanically predictable actuation.

- Backpressure matters: without ACK/FULL, the system degrades under longer drawings.

If you want to run it

The whole project lives in one sketch: plotter.ino in https://github.com/theotarr/plotter.

High-level steps:

- Flash the sketch to an ESP32 (Arduino IDE or PlatformIO).

- Join the configured Wi‑Fi network.

- Open the device IP in a browser.

- Calibrate TL/BR once.

- Draw, submit, iterate.